Growing up, it can be difficult for children to see their parents as anything other than mom and dad.

That was true for Toby Benetti, son of locally-renowned artist Barbara Willson Benetti (1914-88), a Flint native who later called Lake Orion home.

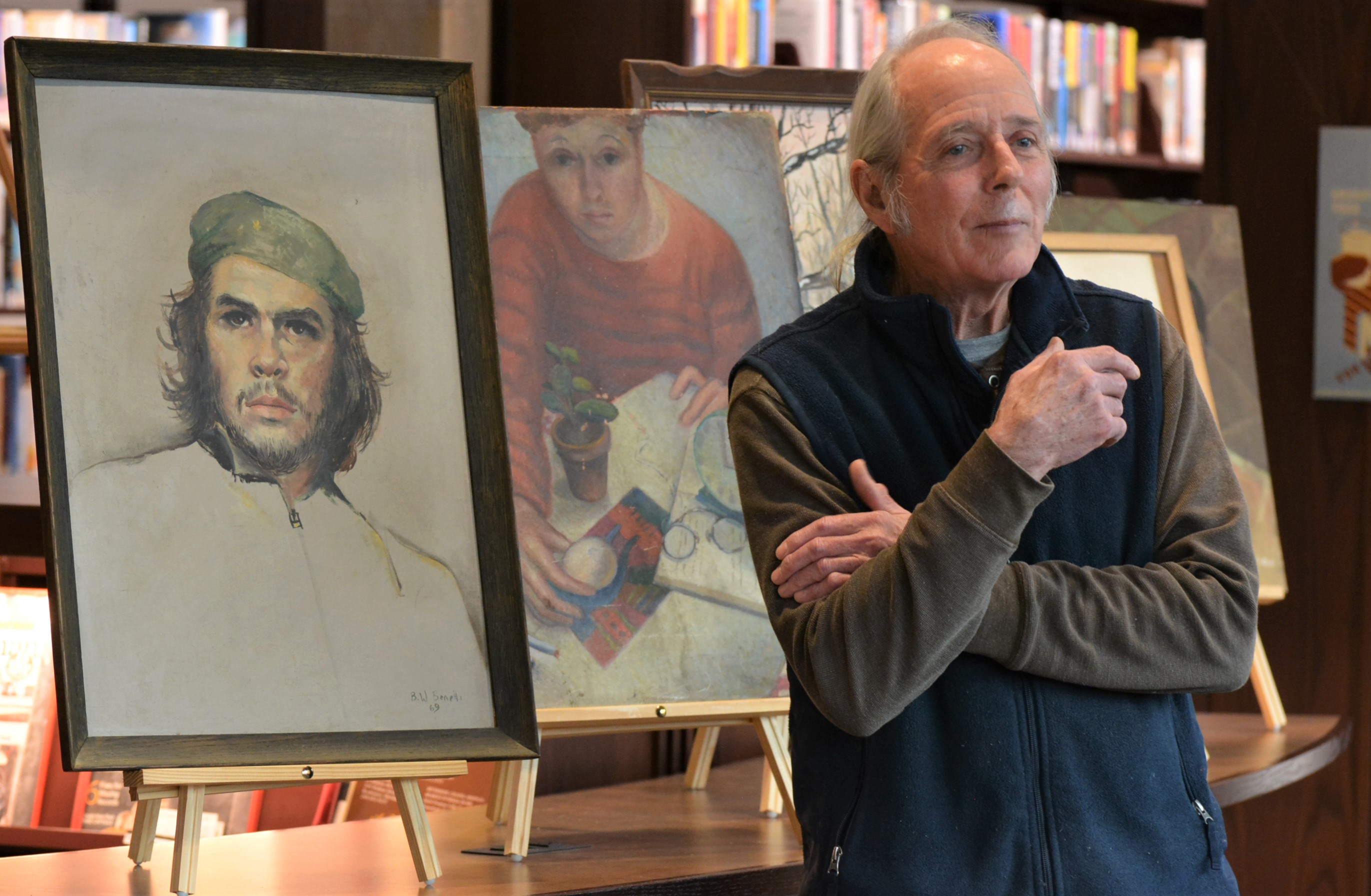

“She was a much more talented artist than I had ever really given her credit for, mainly because she worked in so many different mediums and did all of them very well,” said Toby during a fireside chat about his mother’s work held Friday afternoon at the Oxford Public Library.

Barbara used oil and acrylic paints, water colors, ink, chalk and pencils to create vivid images of people and places.

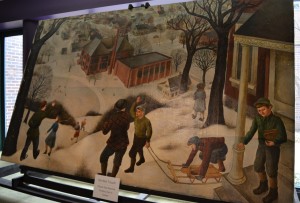

Two large murals she painted in 1938 are on display at the library through the end of February.

The murals, each of which is 7 feet tall and 14 feet wide, depict idealized scenes of Oxford’s past. They usually hang in the Northeast Oakland Historical Museum in downtown Oxford, but they’re on loan to the library thanks to a partnership between the two institutions.

Barbara was commissioned to paint the murals under the Federal Art Project (FAP), which was part of the Works Progress Administration (WPA), later renamed the Work Projects Administration.

The WPA was a New Deal program than ran from 1935-43 under the administration of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. It was meant to put unemployed Americans back to work during the Great Depression. As part of the WPA, many artists, writers, actors and musicians were hired under FAP to provide the public with access to the arts and humanities.

Library Director Bryan Cloutier finds it “mind-blowing” that Oxford is home to two original WPA murals.

“It’s just unheard of that a small town would have something like this,” he said.

Barbara’s murals of old Oxford initially hung in the Washington Street School (the old high school) at the corner of Washington and Church streets. The site is now occupied by Fire Station #1.

Cloutier noted there were originally three murals.

“There was one that supposedly bridged the two (surviving) murals together, (but) the whereabouts of it is unknown to us,” he said.

Cloutier said the murals were displayed at the school for seven years, then taken down. He read an interview with Barbara in which she claimed they were removed because Oxford was “a strong Republican town” that opposed Roosevelt, a Democrat, and his New Deal programs.

After they were taken down, the murals spent years in the school’s basement before they made their way to Barbara’s attic, where they remained until after her death.

“The attic probably wasn’t the best place to store these,” Toby said. “Thank God they were oils because I think they probably would have gotten destroyed between 100-degree summer weather and below-zero (winters).”

After discovering the murals while sorting through his mother’s estate, Toby contacted the Northeast Oakland Historical Museum to see if there was any interest in adding them to its collection.

“I wanted to keep them in the community,” Toby said.

When he showed the murals to the museum’s board members, they were astonished. He said their eyes were as wide as “saucers.”

The donation was eagerly accepted and the museum unveiled the murals to the public during a special event on Feb. 28, 1993.

Cloutier noted because public money was used to pay WPA artists, “the art itself belongs to the federal government” and “can never be sold” to private parties.

Creating art didn’t come easily to Barbara.

“She contended that she did not have natural artistic talent and that everything she did took 10 times the work that somebody (with) natural talent would do,” Toby said.

“None of her children were particularly artistic,” he added. “I’m about as klutzy of an artist as you can possibly imagine.”

Barbara learned her skills by studying at the Flint Institute of Arts. She ended up there after being kicked out of high school during her senior year.

According to Toby, she had a penchant for questioning authority and arguing with teachers who didn’t care for her rebellious, free-thinking ways.

“The problem was my mother was sometimes more well read than the teachers,” he said.

Her parents struck a deal with the school that if she was allowed to return and agreed to not cause any more problems, she could spend her afternoons attending art school.

At the age of 20, Toby said Barbara, who was a “rugged individualist” and “self-professed radical feminist,” went to live and work in an artist collective in Detroit.

Although she never achieved great fame in the art world, Barbara never stopped creating. Toby said after she became a “homemaker,” she divided her time between cooking and painting. He noted she sacrificed her career as an artist to raise a family and her devotion to her children is what helped make him the man he is today.

Cloutier is urging folks to visit the library and view the Oxford murals at eye level before they return to the museum where they hang high off the ground.

“Take advantage of the opportunity to actually see the art up close,” he said.

Leave a Reply