There’s been a large amount of attention given to the K-3 reading programs in Michigan schools over the last several years.

In 2015, the state put $80 million into districts across the state in an effort to improve early literacy.

The following year, the state passed a third-grade reading law, which calls for the retention of third-graders who don’t pass the state assessment in reading in the 2019-20 school year.

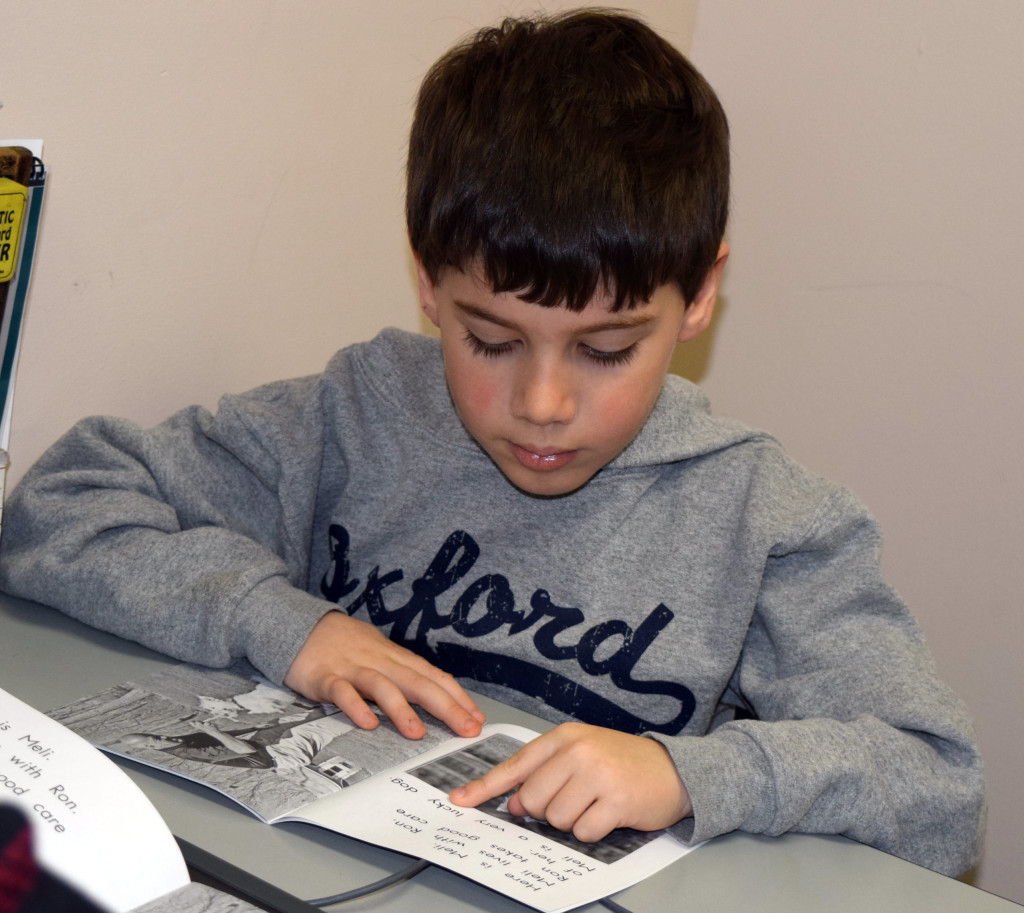

Before the state’s looming deadline two years from now, Oxford Schools administrators and officials have been investing heavily into improving K-3 reading proficiency levels.

Superintendent Tim Throne and Assistant Superintendent of Curriculum and Instruction Ken Weaver recently sat down with The Oxford Leader to discuss these efforts.

In the fall of 2016, school officials spent more than $500,000 of the district’s general fund budget on Lucy Calkins classroom library sets for all kindergarten through fifth-grade classrooms. Additionally, nearly $5,000 was spent on library sets for all developmental kindergarten (DK) students.

These library sets, each of which contained around 500 level-appropriate books, were added to each classroom’s already existing library and were meant to help pique children’s interest in reading, according to Weaver.

“One of the key indicators for a successful reading program is (offering) lots of books that interest kids. They have to have access to books because they are all interested in different things. If it doesn’t interest you, and we’ve all read books that didn’t interest us, it’s very hard to get through. It’s important to have a varied and differentiated library with many different reading materials,” Weaver said. “We also want to alternate between really meeting the students’ (current) reading level and (exceeding) it, to keep them challenged. You’ve got to have books at all levels that you can really do that with the children. Kids’ foundational skills are usually set by third grade. That’s why reading by third grade is really important and why that investment was so important.”

While most students in grades pre-K to three are building important foundational reading skills, most assessment exams issued to fourth-grade students and up focus on reading comprehension, as opposed to reading ability.

To ensure students have the vital foundational skills they need in place by third grade, the district has amped up its efforts to improve early literacy in K-3 students over the last several years, Weaver explained.

Four of the district’s elementary buildings have full-time reading specialists, who are also trained in reading recovery to help students who may already be struggling.

One of these reading specialists is Michelle Mumbrue, who is stationed at Daniel Axford Elementary.

According to Mumbrue, much of her position consists of working on reading recovery with first- and second-grade students whose reading proficiency is below grade level. Through the district’s reading recovery program, students are screened to determine reading proficiency at the beginning and middle of each school year. The 30 lowest-achieving students are entered into the district’s reading recovery program in an effort to get them reading at, or above, their grade level.

The eight lowest-achieving students are given daily one-on-one reading recovery lessons, according to Mumbrue, while the remaining students receive daily lessons in groups of four, for 30 minutes each. The program runs between 12 to 20 weeks, depending on student performance.

“It’s our most intensive reading program,” Mumbrue said.

Oxford Schools invests its at-risk money received from the state into the same mission and has added 16 full- and part-time paraprofessional positions over the last three years, which help with reading intervention at the kindergarten through fifth-grade levels using those funds.

Out of the $80 million the state devoted to early reading efforts in 2015, Oxford Schools received just over $58,000, according to Throne.

This award helped to partially fund three of those part-time reading specialist positions and covered the cost of FastBridge, a computer-adaptive assessment that is used as a screener for students’ reading and math proficiency.

These assessments are given in the fall, winter and spring.

Since FastBridge assessments were first issued in the 2015-16 school year, they have shown an improvement in Oxford’s K-3 reading scores at all of its elementary schools, according to Weaver.

Since the 2015-16 school year, FastBridge results have shown a decline in the number of K-5 Oxford students who scored below the national 30th percentile in reading.

“The FastBridge is a nationally-normed test. It’s recognized, research-based, consistent. They make sure every year they peg the numbers and the percentiles and it’s rock solid. It’s kind of like the SAT or the ACT. You can depend on these results… All of our elementary schools have shown progression through a decreasing number of kids falling below the 30th percentile, which shows what we’ve been doing is working,” Weaver said.

Clear Lake Elementary had 31 K-5 students score below the national 30th percentile in reading when the assessment was first taken in fall 2015-16 compared to 21 students in fall 2017-18. Last fall, the number of Oxford Elementary students who tested below the 30th percentile was cut in half (from 36 students to 17 students) when compared to 2015-16 results. Other schools which showed a reduction in students scoring below the 30th percentile were Daniel Axford (which decreased from 27 students to 17 students), Lakeville (which decreased from 47 to 31 students) and Leonard Elementary (decreased from 23 to 15 students).

Oxford students who fall below the 30th percentile on the FastBridge reading test are identified for further testing and often required to receive an Individual Reading Improvement Plan (IRIP) from the district, which establishes goals and methods to help improve their reading proficiency.

Since everyone learns differently, Weaver said the district also teaches young students both phonics and whole word language reading principles.

When asked ‘what’s next’ in the quest to improve early literacy within the district, Weaver said school administrators have formed a committee this year to improve Oxford’s Multi-tiered System of Support (MTSS).

“The MTSS is a system that helps us provide extra support for students through interventions and other means. It’s how you identify kids and recognize them, so you don’t let them slip through the cracks, so to speak. We’re really working on that,” Weaver explained.

When it comes to improving early literacy within the district, Weaver added that much of that improvement starts at home.

“Ages 0-5 are extremely important for a child when it comes to learning to read . . . The amount of words they hear, how big their vocabulary is, how many times they’re read to . . . It’s so important,” said Weaver. “Parents are, first and foremost, their child’s teacher. They’re the first teacher that they’ll have and they will be the last teacher that they’ll have in life. The kids need their parents to read to them constantly, engage in conversation with them to help them develop their vocabulary.”

Leave a Reply