‘Stress, Trauma and the Path to Resiliency’

By James Hanlon

Leader Staff Writer

Oxford Community Schools hosted a webinar by a trauma specialist last month to help parents understand different kinds of trauma and how to support their children after the Nov. 30 shooting at Oxford High School.

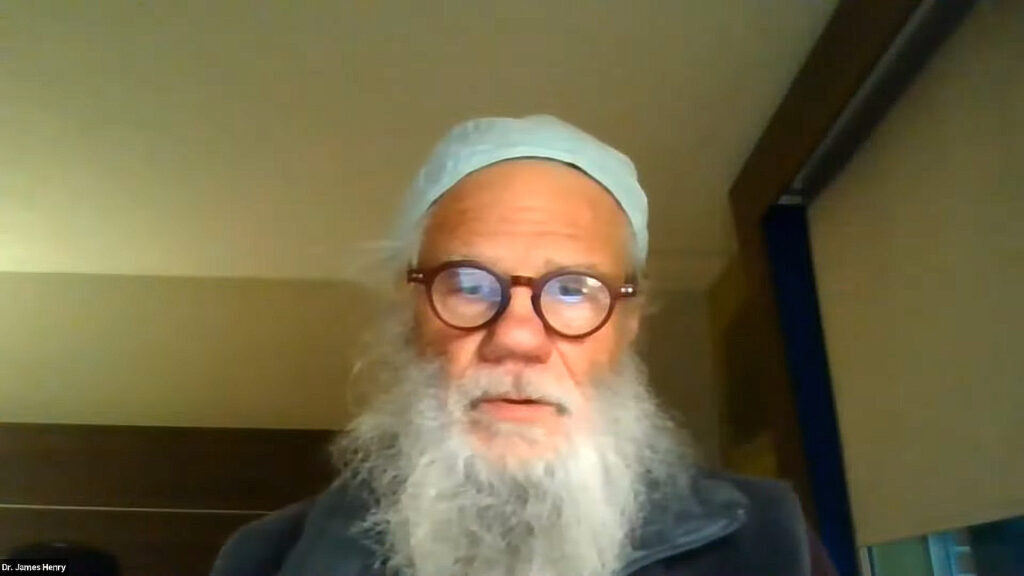

James Henry, co-founder and project director for Western Michigan University’s Children’s Trauma Assessment Center, led the sessions. Over the last 42 years, Henry has worked with thousands of children who have been through all kinds of traumatic events. In recent weeks he has worked with OHS staff and students directly.

“Trauma isn’t resolved in a day, or a week or a month,” Henry said. “It’s an ongoing process. And we can learn to manage that more and more, but it still spikes.”

The first step parents can take in helping their children heal the trauma is to acknowledge the pain. This goes against our culture, which likes to pretend that pain doesn’t exist – or if it does, it doesn’t bother us.

“One of the most important things you can do for your kids is to be able to communicate that it does bother you,” Henry said. “You’re hurt, or you’re angry, or you’re sad or you’re confused. But it does affect you.”

The other thing parents can do is to just listen and be with. “Children need to be heard, not told what they need.”

Henry went on to describe how trauma and grief might show up. These experiences impact people differently “based on their history, their temperament, their genetics and how they experienced the event that happened. So it’s not one-size fits all.”

Five normal reactions to grief are shock (or denial), anger, bargaining, sadness and acceptance – but not necessarily in that order. “These five areas, they move around,” he pointed in a circle, “they’re not linear . . . they dart back and forth from one to another.”

But beyond grief is trauma. Trauma is defined as “an overwhelming event or events that render a child helpless, powerless, creating a threat of harm or loss.” That event is then internalized and continues to impact how they perceive themselves, others and the world. In turn, those perceptions can affect the child’s development.

“Trauma changes perception. And it’s important to know that when I change my perception because of what happened, it becomes my reality, at least temporarily.”

The severity of trauma depends on several factors including proximity to the event, past trauma and predispositions for anxiety. Those who did not experience the traumatic event directly can still experience “secondary trauma” if they hear about it from a loved one who did experience it, especially their own child.

Trauma can impact four categories of experience: cognitive, social, emotional and physical. It’s important to name these categories, Henry said, because these are normal responses to what happened.

Cognitively, there can be a negativity bias, a tendency to blame, all-or-nothing thinking with no complexity, loss of critical thinking and a focus on threats.

Survivor’s guilt is a normal cognitive distortion. Survivors of a traumatic event might have recurring thoughts that they could or should have done something, or that it was their fault that it happened.

You can’t take that away, but you can name it and be with it. “As we give kids language, rather than just saying ‘it’s not your fault’ and expecting them to believe that – they can’t at this point, because they’re trying to make meaning and sense of things – sometimes the only way to make sense about it is if we see ourselves as the person that could have stopped it or somehow made it different. And that hurts, and that’s grief. But that’s where your kids need you as parents to be there with them in that grief.”

Trauma can impact kids socially, leading to withdrawal and less collaboration with others. They might try to isolate in order to feel safe. That’s “something to be aware of,” Henry said, “because it can really affect functioning.”

Emotionally, they might feel helplessness, hopelessness or overwhelmed. “Helplessness is a normal response to trauma, to secondary trauma, but where it becomes harmful or unhealthy is when it becomes my perception of everything . . . then I become the victim, in a sense, rather than to feel empowered.”

And physically, there might be headaches, stomachaches, tense muscles, fatigue or sleep difficulties.

Lastly, Henry suggested ways to build resiliency. Rituals and routines help form a common framework for parents, students and staff to build resiliency by returning to a normal level of everyday stress. That’s why it’s important to go back to school sooner than later.

As students return, they can regain confidence through a sense of mastery and control. Ultimately, the goal is to recover the belief that they have some control over their environment, that they are not victimized, but a survivor. There’s a sense of moving forward and empowerment.

They can tap into that empowerment to meet adversity. “It’s not about ignoring the experience or pretending it didn’t happen . . . It’s about being with and moving forward in a way that heals and addresses rather than minimizes or pretends.”

But the most important component of resiliency, Henry said, is connection. We can support our children by showing them they are not alone.

Leave a Reply