Atomic bombs played a significant role in Steven Maczko’s younger days.

They most likely saved his life during World War II and they made him a part of history during the Cold War arms race that followed.

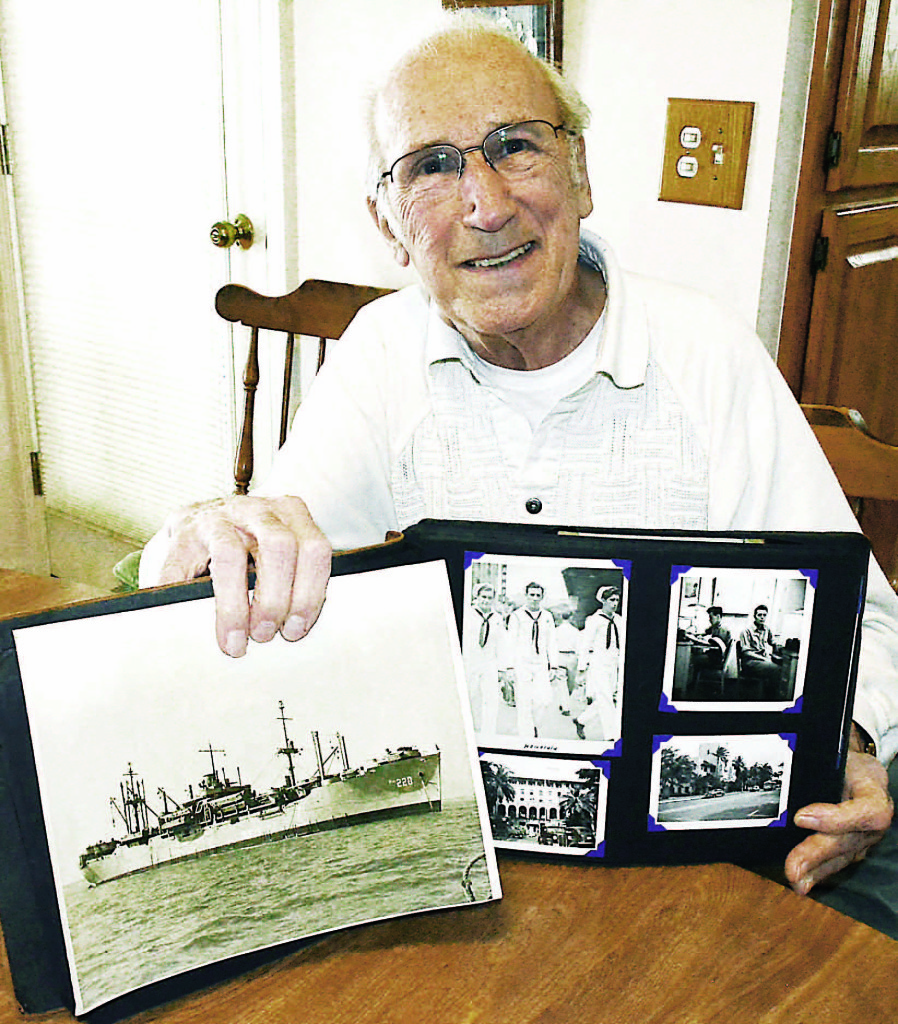

Last week, the 91-year-old Oxford Village resident sat down with this reporter to talk about the A-bomb, as it used to be known, and his experiences in the United States Navy from October 1944 to October 1947.

Right off the bat, Maczko stressed his gratitude to the Navy for all it did for him.

“I’m totally a Navy man,” he said. “The Navy treated me great (and) educated me when I got out. I don’t regret anything.”

After Maczko entered the service and finished boot camp at the Great Lakes Naval Training Center in Illinois, it became clear he was going to be part of the planned invasion of Japan.

In January 1945, he was sent to Fort Pierce in Florida for a little over four months of “intensive training.”

He was being prepared for amphibious operations involving a Landing Craft, Vehicle, Personnel (or LCVP) – a boat designed to deliver troops from sea to shore during an assault.

But Maczko was also learning survival skills such as hand-to-hand combat.

“They knew the Japanese at that time were not going to surrender. It was going to be rough,” he said. “I was scared. I was convinced that nothing good would come of it.”

After Florida, Maczko headed to Norfolk, Virginia where he boarded the USS LST-307, which had previously been used in the June 1944 invasion of Normandy. LST stands for Landing Ship, Tank, a vessel created by the Allies during WWII to support amphibious operations by transporting tanks, vehicles, supplies and troops directly to shore without using piers or docks.

Maczko wasn’t at sea very long when some big news hit.

“The war was over when we reached New Orleans, Louisiana,” he said.

On Aug. 6, 1945, the U.S. dropped an atomic bomb on the Japanese city of Hiroshima. Three days later, a second atomic bomb was used on Nagasaki.

As a result of these two bombings, Japan surrendered, rendering the proposed invasion of the Axis power, codenamed Operation Downfall, unnecessary.

Controversy and debate over the atomic bomb’s use continues to this day, but there’s no doubt in Maczko’s mind that it was the right thing to do.

“I was very happy because they told us there would probably be a million sailors, (soldiers), pilots (and) Marines killed because the Japanese would not surrender,” he said. “I could see they were right based on (what happened at) Okinawa.”

Codenamed Operation Iceberg, the invasion of the Japanese island of Okinawa was the largest amphibious landing in the Pacific Theater. During the three-month battle that began in April 1945, the U.S. sustained more than 49,000 casualties, of which 12,520 were deaths.

Maczko wasn’t anxious to become part of some casualty count, so he’s glad the atomic bombs eliminated the need to invade Japan.

“Thank you, Harry S. Truman for dropping the bomb on Japan,” he said. “He took a lot of criticism (for that decision). A lot of people to this day still criticize him. But he’s got my heartfelt thanks because I would have been in the midst of (the invasion) and who knows? I might not be here today.”

And neither would the five daughters and one son he went on to have following the war with his late wife Donna.

“I think of the good lives they’ve had that they would not have had (if I had died),” Maczko said. “I’m very, very happy that Truman did what he did. A lot of (Japanese) people were killed or maimed for life (by the atomic bomb), but we didn’t start the war, either. We were protecting ourselves.”

Maczko did eventually make it to Japan as his ship, LST-307, was assigned to occupation service in the Far East from October 1945 to March 1946.

During his time in the former enemy nation, Maczko said he “didn’t get to see an awful lot” as many areas were restricted.

“What I did see was Tokyo flattened,” he said. “You almost had to feel sorry for them, in a way – what they went through during and after the war. But they bombed Pearl Harbor and a lot of men were lost there (along with a) lot of ships. So, you can’t feel too sorry (for them).”

Even though the war was over, Maczko did get shot at in Japan while walking around with a group of his fellow sailors. He later learned it was because they were walking through a Japanese cemetery that was off-limits.

“You had to be very, very careful where you went and what you did,” Maczko said.

Following WWII, Maczko became part of Cold War history when he participated in the 1946 nuclear tests at Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands.

Codenamed Operation Crossroads, two atomic bombs were detonated in order to study their effects on ships, equipment and materials. It was the first time nuclear weapons were deployed since the attacks on Japan.

A fleet of more than 90 vessels, including U.S. ships and submarines along with captured German and Japanese ships, was assembled in Bikini Lagoon as a target. They were loaded with scientific instruments and more than 5,500 live, experimental animals.

“They had a big circle of ships,” Maczko said.

According to his military record, he served aboard four of the target ships at various times from 1946-47 – USS Gilliam (APA-57), USS Brule (APA-66), USS Niagara and USS Geneva (APA-86).

The target fleet was supported by another fleet of more than 150 ships that provided quarters, experimental stations and workshops for most of the 42,000 military and civilian personnel, Maczko included, that took part in the tests, according to the fact sheet issued by the U.S. Defense Nuclear Agency (DNA) in 1984.

On July 1, the first bomb was dropped from a B-29 and detonated over the target fleet at an altitude of 520 feet, according to the DNA fact sheet. It sunk five ships.

The second test, which occurred on July 25, involved suspending a bomb beneath an auxiliary craft in the midst of the fleet and detonating it 90 feet underwater, according to the DNA fact sheet. It sank eight vessels and damaged more ships than the first test.

“A lot of the ships were sunk. It was that powerful. It just capsized them,” Maczko said.

Each bomb had a yield of 23 kilotons. To put that in perspective, the bomb dropped on Hiroshima was 15 kilotons.

Maczko recalled being about 17 miles away when the bombs went off. They didn’t make much of an impression on him.

“I didn’t see a thing,” he said. “I looked when they told us we could look. We had colored-glasses that they gave us (for protection). I couldn’t see a thing. They said you could feel a little pressure. I didn’t feel it.”

Two things stood out in Maczko’s mind about his role in Operation Crossroads.

One was the potential negative health effects of being exposed to radiation. After working aboard one of the target ships following one of the tests, Maczko said he and others were told to get off because it wasn’t safe and by the way, “you might be sterile.”

“Well, I went on to have six kids, so I wasn’t sterile,” he said. “But it scared the hell out of everybody.”

He also “resented” it.

“I wanted a family,” Maczko explained. “What the hell did you send us back on that ship for if you knew that? Fortunately, it didn’t happen.”

The other thing Maczko recalled about the atomic testing experience was the severe depression he felt due to the miserable conditions.

“It was a hellhole,” he said. “You couldn’t walk on the (ship’s) deck with your bare feet (because) you’d get blisters. It was that hot. You could go swimming, but there would be a guy with a rifle ready to shoot the sharks in the water.”

“It was very, very depressing for a young kid. I didn’t know I could get that depressed,” Maczko noted.

Despite this, looking back at his time in the Navy, Maczko is grateful that it gave a young man who “never went any place” the opportunity “to see the world.”

And as was mentioned earlier, his naval service paid for his college education. He earned a degree from Walsh College and went on to have a lengthy career in accounting that ended when he retired at the age of 76.

He and Donna were married for 65 years. They moved to the Oxford Lakes subdivision 21 years ago.

Donna passed away in March 2015.

“I still miss her,” he said.

One of Maczko’s daughters wanted him to move closer to her in Ann Arbor, but he has no desire to leave his spectacular view of Oxford Lake or his neighbors, who take him out to dinner once a week and clear his snow in the winter.

“I have great people that look after me and take care of me,” he said. “I’m happy where I’m at. As long as I can be (self-sufficient), I’m going to stay here.”

I always knew my father was a legend, now every else knows, too! Thank you for a great article!